Hill JJ, Keating JL, Physical Therapy Journal, 95 (2015) 507–516.

Abstracted by: Russell Hanks, PT, COMT, Anchorage, AK — Fellowship Candidate, IAOM-US Fellowship Program & Jean-Michel Brismée, PT, ScD, Fellowship Director, IAOM-US Fellowship program.

This prospective multicenter cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared education and regular specific back exercises with education alone on the incidence of low back pain (LBP) in children aged 8 to 11 years. The research available1 appears to indicate that regular specific back exercises when combined with education may reduce episodes of LBP and lifetime first episodes of LBP when compared with education alone. This paper attempted to examine how children stay compliant to an exercise routine and whether or not they would make it an ongoing part of their daily practice. This study also examined the factors that lead to exercise compliance.

The prevalence of LBP increases with age, starting as young as 9 years of age and reaching similar prevalence as reported for adults by 15 years of age.2, 3 LBP in adolescence predicts LBP in adulthood, 4, 5 signaling a role for primary prevention of the lifetime first episode of LBP.3, 6 The only risk factor for LBP that has been validated in independent studies in adults is a history of previous LBP.3, 7-11 Exercise appears to be helpful in reducing the recurrence of LBP in adults,12 and may influence future spine health of young people with a history of LBP.13,14 Reviews of interventions to improve spinal knowledge, change movement behavior and reduce the prevalence of LBP in children showed potential benefits, but evidence to support their effects is limited.15, 16

Methods

This was an observational study of compliance to exercise. It was embedded in a prospective RCT comparing education and daily exercise with education alone on LBP in children (aged 8 to 11 years) in primary schools in New Zealand for 270 days between April and December 2011. Schools were enrolled in the MySpine program and were allocated using randomization with concealment to an exercise and education group (intervention) or to education alone (control).

The children in the study ranged in age from 8 to 11 years and were able to follow simple instructions, complete a child-friendly survey and whose parents gave their informed consent. Children were excluded if they were not able to do the exercises due to spinal pathologies, neurological disorders, injuries, or physical disabilities for which movement was a contraindication or prevented standing unilaterally safely and independently.

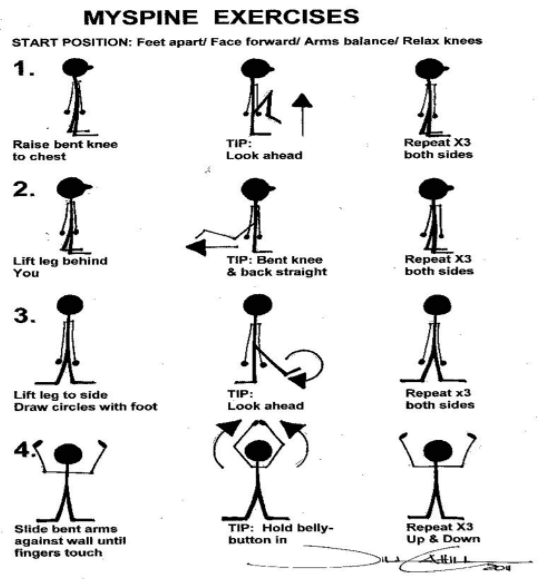

The primary researcher, a physical therapist, visited each group in the study (intervention or control) seven times over the 270-day period. A randomization officer assigned the students to each of the groups. Figure 1 summarizes the intervention (MySpine program) and control conditions, along with the 4 exercises shown to the intervention group. Back awareness and taking responsibility for “MySpine” were taught and reinforced at each session within each of the control and intervention groups. The range of motion exercises encouraged movement, could be performed without supervision, were meant to be easy to remember and could be added to any existing exercise routine. Students were encouraged to perform the exercises three times per day. Instruction was also provided to encourage compliance to the exercise program.

Children were given surveys to determine a history of low back pain (day 1) or episode of low back pain when the researcher visited the schools on days 7, 21, 49, 105, 161, and 270. The duration of low back pain was tracked and categorized in shorter episodes (1-2 days) and longer episodes (> 3 days). They were also asked about their compliance to the exercise, the frequency of performance and their reasons for non-adherence.

MySpine Program

Both Groups:

- Introduction to the MySpine program (15 minutes)

- Baseline Survey

- Back awareness education session. “Taking responsibility for your spine.” (15 minutes)

- Anatomy of the spine

- What is low back pain?

- Movement versus static postures

- Taking responsibility for your spine – “It’s about what you can do.”

- Handy hints – advise children to “stand tall, shoulders square, chin in, keep moving, don’t slouch.”

- Question time (5 minutes)

Intervention Group:

- Demonstrate 4 back exercises (see below)

- Emphasize moving the back through the full range of flexion, extension, and lateral flexion movements, repetition, and awareness of back movement. Advise to repeat 3x/day.

- Children demonstrate exercises

- Exercises checked

- Performance difficulties addressed using feedback and demonstration

Results

There were 764 children in 7 participating schools meeting the criteria for the study. There were no significant differences between the groups in regards to age, episodes of LBP, or response attrition. During the trial, 35% of the intervention group and 28% of the control group reported on LBP episodes. Children with a history of LBP had greater odds of reporting pain during the study. Short duration LBP (1-2 days) occurred in 72% in the control groups and 62% in the intervention groups. There were no significant differences between groups for LBP episode durations and there was no significant effect on the frequency of exercises performed for episodes of LBP.

Discussion

Children in the exercise group reported fewer episodes of LBP and fewer lifetime first episodes of LBP than those in the control group. At the start of the study, 47% of the children reported a previous episode of LBP. The researchers observed a decrease of 23% at day 7 in episodes of LBP to 13% at day 270 in the intervention group and 33% to 24% in the control group, respectively. Children in the exercise group were also less likely to report a lifetime first episode of LBP and experience a longer time to onset of a first episode when one did occur.

It has been suggested that it may be inappropriate to apply adult definitions of LBP when assessing children17 and that children may conceptualize pain in ways that differ from adults.18 A reduction in LBP was reported across both groups in spite of compliance to the exercises declining across the study. The researchers could not confidently attribute the results to exercise participation. They stated that likely there was not a physiological effect from the four exercises but felt that paying attention to the children, educating them about the spine and LBP and talking about the importance of movement had a therapeutic effect on the children.

In conclusion, the program presented in this study may reduce episodes of LBP in children ages 8-11 years, however it is unlikely the results can be attributed to the exercises alone but also the education provided. Additional studies are needed to validate these findings.

IAOM Comment:

Low back pain in children is becoming more common and as indicated in the references of this study, it is often a predictor of LBP in adulthood.4,5 I think the important point made in this study was that it wasn’t either exercise or education that made the difference, it was both. I don’t think it comes as a surprise to anyone with children that compliance to the exercises declined over time. In fact, I think we could safely assume that happens with all age groups. We don’t need a study to prove what most of us have seen in our practices.

Increasing activity levels in children is important. It is disturbing that LBP is becoming more common but not surprising given the trends seen with children spending more time in front of screens.19 I think it is important to note that any exercise will become routine for most people over time. Regardless of the effectiveness of the 4 exercises in this program, asking a child to be compliant over a 6-month period, especially if they didn’t have back pain, seems unlikely. I think it is a challenge for physical therapists to have our patients stay compliant with their home exercise programs. In this study, education was also an important component in the success of reducing the onset of back pain. I try to ask myself the following four questions when prescribing a home program: (1) What does the patient need to know? (2) Why do they need to know it? (3) What do they need to do?; and (4) Why do they need to do it?

Education is important, but ultimately, what does the patient need to know about what is going on with their body? This will be dependent on what the patient wants to know.20 Some patients want to know everything and others, not so much. Once you have determined what they need to know, it is important to help them understand why. This makes the information relevant. It the information stays irrelevant, then it is not a felt need and will be ignored. Next, what do they need to do? This is the exercise, or whatever else makes up your home program. Is it easy to follow? Have you included a picture, or video from their phone, or handout of some kind? This helps with compliance.21 Lastly, why do they need to do it? Assisting patients with understanding why they are doing a home program helps them understand the relevance of the exercise. It also helps them engage in what problem is being addressed and how to measure their improvement. Compliance is a challenge but I’ve found asking these four questions helps my patients be more successful.

References

1 Hill JJ, Keating JL. Daily exercises and education for preventing low back pain in children: cluster randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2015; 95:507–16.

2 Hill JJ, Keating JL. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of low back pain in children. Phys Ther Rev 2009; 14:272–84.

3 Burton AK, Balague F, Cardon G, Eriksen HR, Henrotin Y, Lahad A, et al. How to prevent low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005; 19:541–55.

4 Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche C. The course of low back pain from adolescence to adulthood: eight-year follow-up of9600 twins. Spine 2006; 31:468–72.

5 Jeffries LJ, Milanese SF, Grimmer-Somers KA. Epidemiology of adolescent spinal pain: a systematic overview of the research literature. Spine 2007; 32:2630–7.

6 Cardon G, Balague F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in school children. What is the evidence. Eur Spine J 2004; 13:663–79.

7 Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C. Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J 2003; 12:149–65.

8 Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2005; 90:312–6.

9 Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C,Kyvik KO. Is comorbidity in adolescence a predictor for adult low backpain? A prospective study of a young population. BMC Musculoskel Dis 2006; 7:29.

10 Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsoe G, Kjer J, Harreby M, Neergaard K, et al. Are radiologic changes in the thoracic and lumbar spine of adolescents’ risk factors for low back pain in adults? A 25-year prospective cohort study of 640 school children. Spine 1995; 20:2298–302.

11 Hill JJ, Keating JL. Risk factors for the first episode of low back pain in children are infrequently validated across samples and conditions: a systematic review. J Physiother 2010; 56:237–44.

12 Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, Koes BW. Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. [Summary for patients in Ann Intern Med 2005;142: I71]. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:765–75.

13 Jones M, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan V. The efficacy of exercise as an intervention to treat recurrent nonspecific low back pain in adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2007;19:349–59.

14 Fanucchi GL, Stewart A, Jordaan R, Becker P. Exercise reduces the intensity and prevalence of low back pain in 12–13-year-old children: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother 2009; 55:97–104.

15 Steele EJMPHB, Dawson APGB, Hiller JEP. School-based interventions for spinal pain: a systematic review. Spine 2006; 31:226–33.

16 Cardon G, Balague F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in school children. What is the evidence? Eur Spine J 2004; 13:663–79.

17 Balague´ F, Dudler J, Nordin M. Low-back pain in children. Lancet. 2003; 361:1403–1404.

18 Burton AK, Mu¨ller G, Balague´ F, et al; on behalf of the COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Prevention in Low Back Pain. European guidelines for prevention in low back pain. November 2004. Available at: http://www.backpaineurope.org/web/files/WG3_Guidelines.pdf. Accessed September 2014.

19 American Academy of Pediatrics. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics 2001; 107:423–426 [PubMed]

20 Shekhawat L et.al. Does the cancer patient want to know? Results from a study in an Indian tertiary cancer center. South Asian J Cancer 2013; 2:57-61.

21 Zhabenko O. et.al. Supporting Homework Compliance in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Essential Features of Mobile Apps. JMIR Ment Health 2017 4:e20. 10.2196/mental.5283