Blomgren J, Strandell E, Jull G, Vikman I, Röijezon U. Effects of deep cervical flexor training on impaired physiological functions associated with chronic neck pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:415.

Abstracted by:

Brent Denny, DPT, ScD, COMT Marble Falls, TX – Fellowship Candidate, IAOM-US Fellowship Program & Jean-Michel Brismée, PT, ScD, Fellowship Director, IAOM-US Fellowship program.

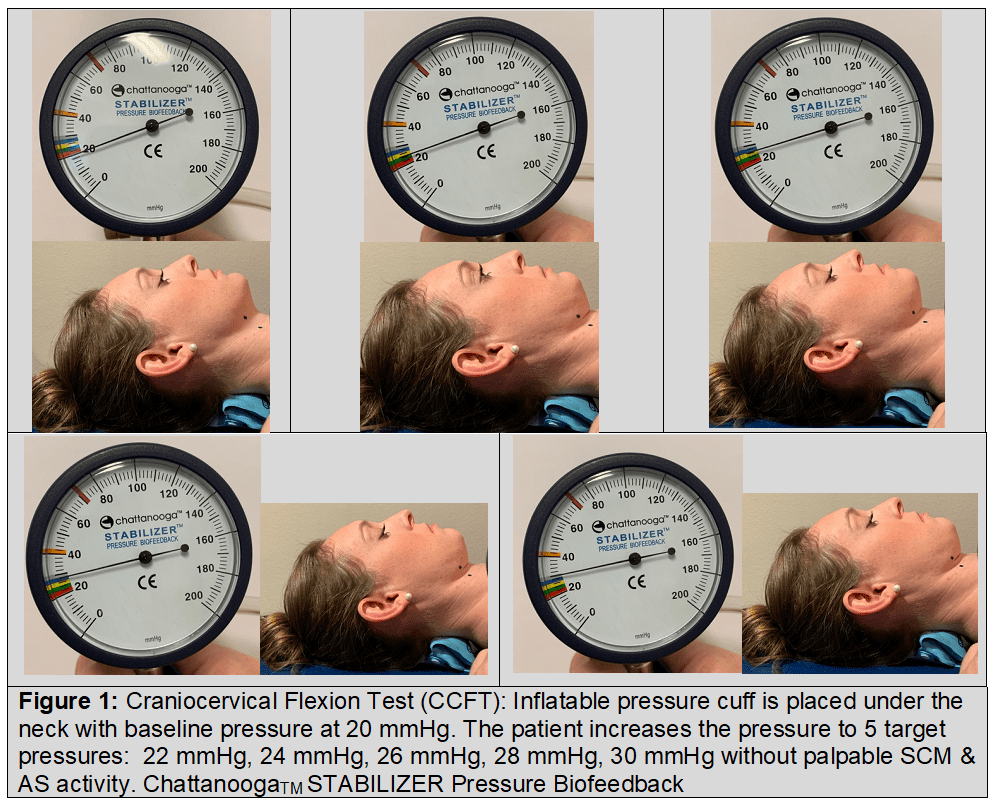

Context: Studies focused on neck pain, a high contributor to years lived with disability, have revealed sensorimotor dysfunctions including hypoactive, weak deep cervical flexors (DCF), hyperactive superficial sternocleidomastoid & anterior scalenes, delayed reflexive activation, proprioception, and postural stability. Studies evaluating the efficacy of conservative treatments, often involving exercise prescription, use pain as the primary metric. No systematic review, to this point, has assessed effectiveness using other physiological metrics.

Objective: This review purposes to assess DCF training effects on “impaired physiological functions, cervical neuromuscular function, muscle size, kinematics, and kinetics” in chronic (recurrent) neck pain patients.

Type of Review: Systematic review with meta-analysis

Methods: Online search engines including Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, PubMed were used to search for randomized controlled trials (no intervention control group) and randomized clinical trials (intervention compared to other intervention(s) from inception to January 2018. Twelve studies were deemed appropriate for review.

Details of Paper: Twelve studies consisted of 502 neck pain participants.

Conclusion: One exercise mode is insufficient to mitigate all the physiological dysfunctions present in neck pain sufferers. Neuromuscular coordination dysfunctions may largely be addressed using DCF training; however, global strength and endurance deficits required higher intensity training. Other Sensorimotor deficits, particularly Joint Position Change (JPS) while improved with DCF training, may better be addressed with specific proprioception training.

IAOM-US Commentary:

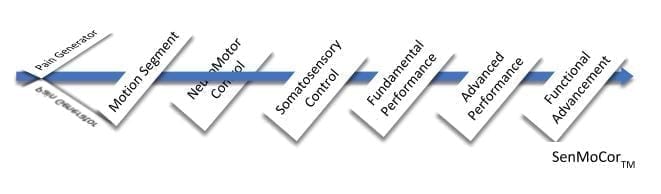

The IAOM-US advocates a pragmatic and precise approach to patient care whereby interventions are chosen based on both clinical and functional examinations findings. Clinical examinations are ideally suited to identify specific pain generators, and joint/tissue dysfunctions. Functional examinations begin to identify sensorimotor and movement pattern dysfunctions. Patient goals, tissue irritability, sensorimotor capability, and gross movement pattern competency guide treatment decisions. Regarding neck pain, the IAOM-US recognizes that specific cervical treatments must be contextualized within the upper quarter and eventually to total body control. The following graphic represents an organization of treatment progressions.

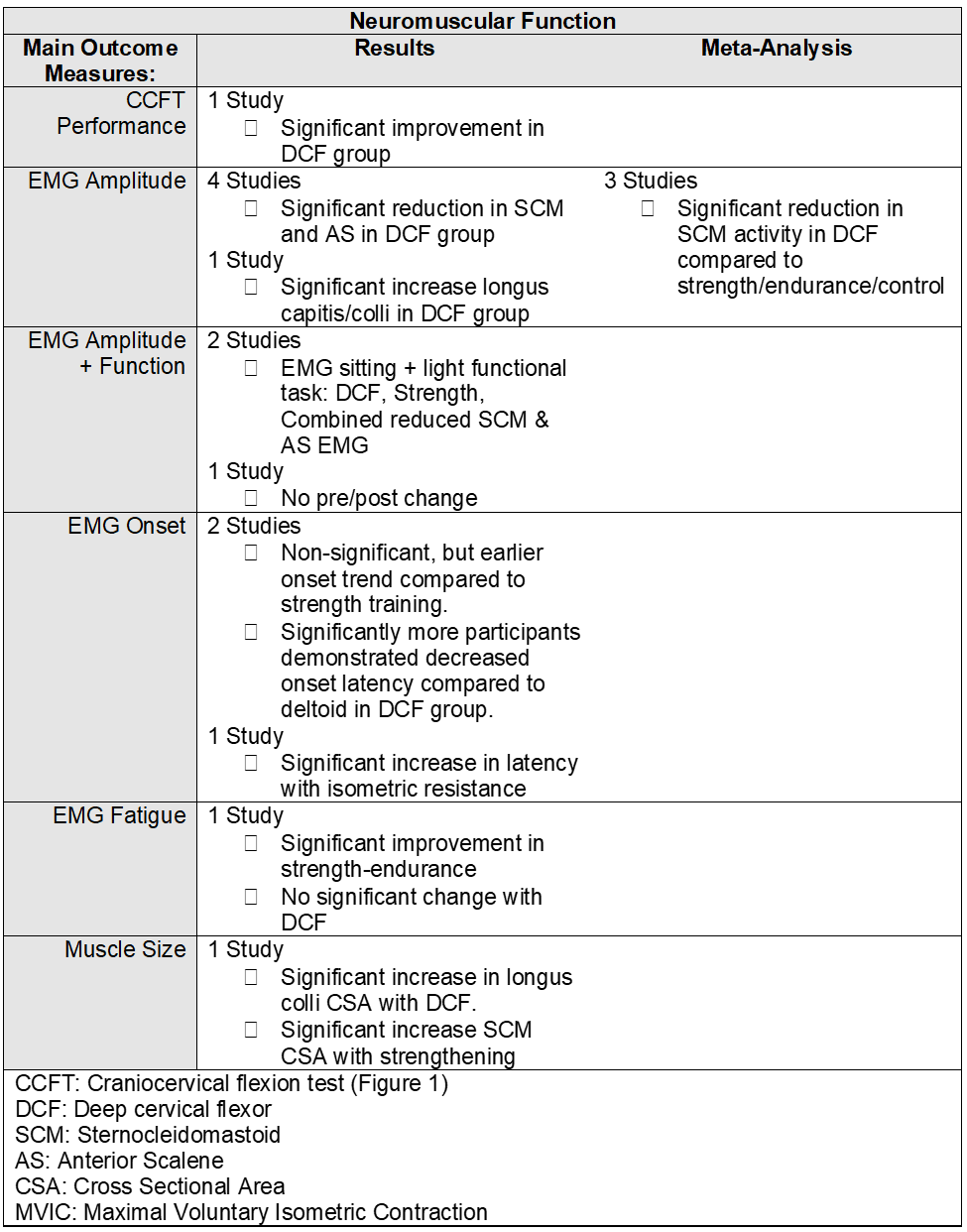

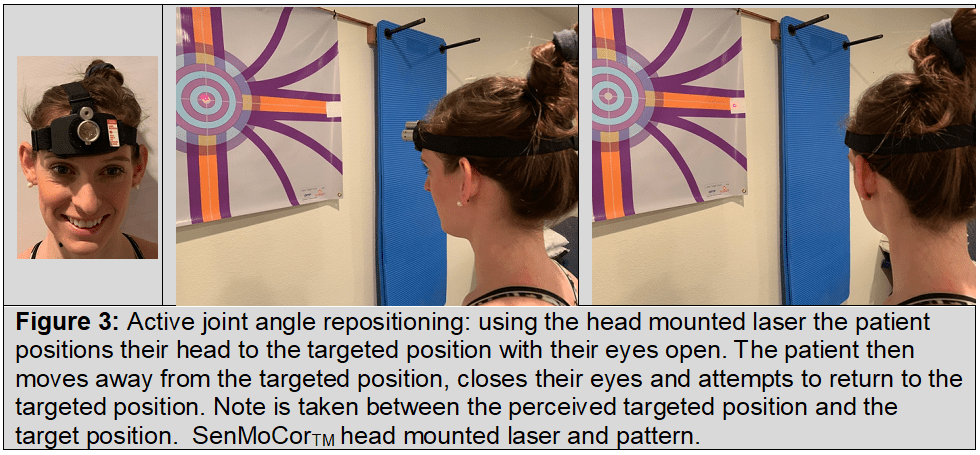

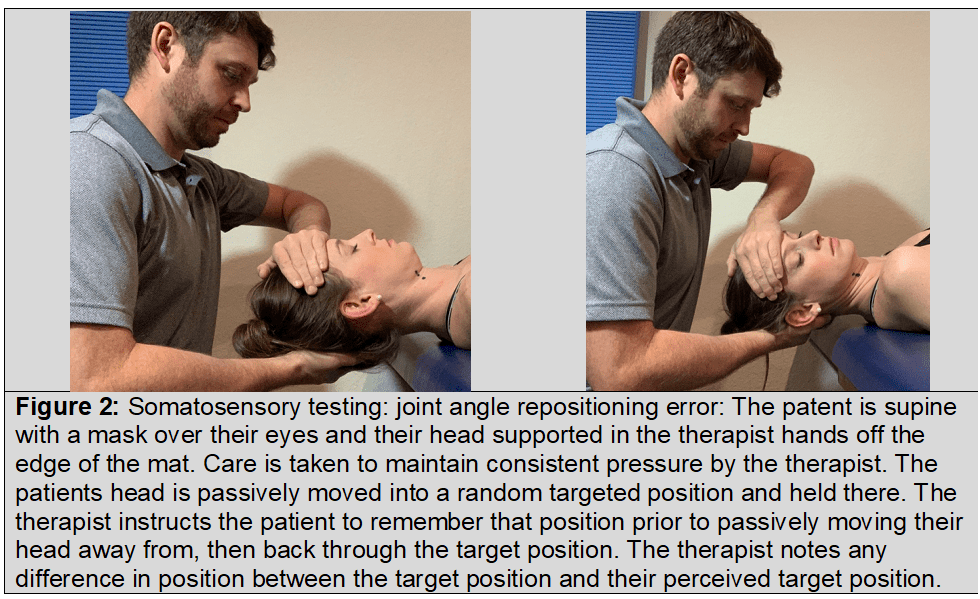

Healthy deep cervical flexors (DCF), specifically the longus capitus and longus colli are fundamental to cervical neuromotor control. Neuromotor dysfunctions, as described by Blomgren et al 2018, include delayed & diminished DCF feedforward activity. The global muscles including the sternocleidomastoid and anterior scalenes are prone to compensatory hyper-activity in neck pain sufferers (Falla et al 2004 a, Falla et al 2004 b, Lindstrom et al 2011). Thus, it is the stance of IAOM-US that global muscle training be de-emphasized early in the rehabilitation process. The craniocervical flexion test (CCFT), as reported by Blomgren et al 2018 (see Figure 1), is clinically useful to determine DCF function and global compensation. Somatosensory, or feedback control, includes reflexive activation, proprioception (Figure 2), postural stability, and postural control. Interestingly, DCF training using the CCFT process was reported effective to address not only neuromuscular, but also somatosensory proprioceptive and reflexive activation dysfunctions (Jull et al 2007). While helpful, specific proprioception training, such as described by Revel et al (1994) focusing of “eye-neck” coordination was more efficacious compared to CCFT training (Revel et al 1994; Jull et al 2007).

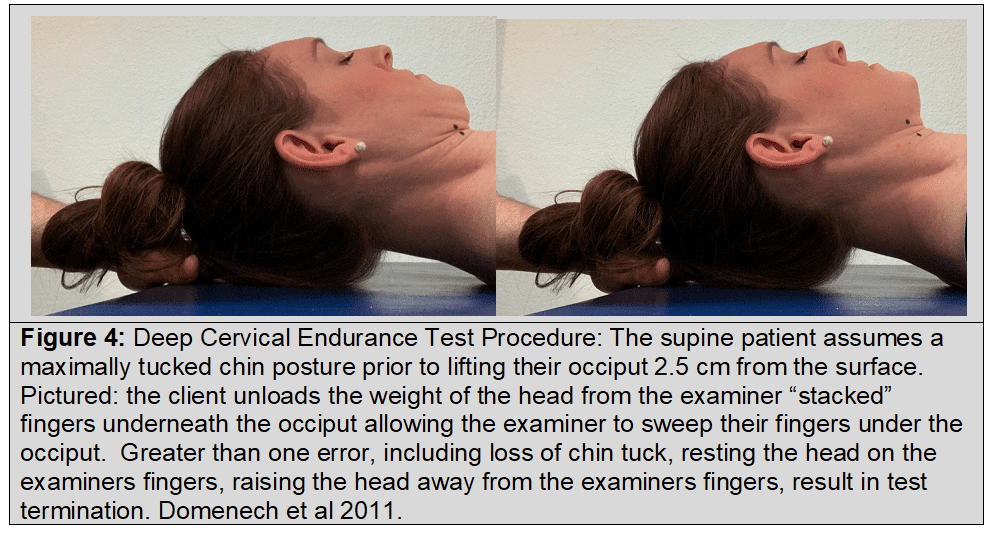

The IAOM-US suggests the question is not “if” the CCFT and training are appropriate, rather “when” they are appropriate. Consider a patient with a primary pain generator involving the cervical disc with upper cervical segmental stiffness in the posterior C0-1 capsules. This is a typical patient whereby cervical retraction is often provocative and craniocervical flexion is impaired. Initially, treatment may focus on reducing pain generator sensitivity, restoring segmental mobility, and reducing myofascial dysfunctions with general manual therapy, joint specific manual therapy, and augmented, patient performed mobility training. Motor imagery of “think look down” and eyes movement have been shown to facilitate DNF EMG activity (Sizer P, SenMoCorTM 2012, Hildago-Perez et al 2015, Moon et al 2015, Park et al 2018 and may be used to augment CCFT training. As the patient advances away from a pain dominant state and is able to perform pain free craniocervical flexion then CCFT testing and training may be initiated. Objective goals using the CCFT will help track progress. Somatosensory training (Figure 3) may be further enhanced using a head mounted laser to provide feedback during static postural control and dynamic cervical control. Furthermore, eyewear that constrains peripheral vision is useful for proprioceptive training (Revel et al 1994). Addressing the pain generator(s), motion segment, neuromotor and somatosensory deficits will provide a solid sensorimotor foundation that complex movements and loading may be built upon. Once sufficient progress is achieved, and if appropriate, rehabilitation may then shift focus on restoring DNF endurance testing and treatment (Figure 4). Deep neck flexor endurance normative ranges have been reported to be 40 seconds in men and 30 seconds in women without neck pain (Domenech et al 2011).

Global cervical strengthening should be initiated, depending on the patients’ goals, once their local neuromuscular and somatosensory dysfunctions have been appropriately addressed. While the above discussion is focused on the cervical spine, concurrent upper quarter training targeting thoracic, scapulothoracic, and glenohumeral dysfunctions should be addressed to return optimal upper quarter function (Silva et al 2018).

The IAOM-US commends Blomgren et al 2018 as this illuminating systematic review with meta-analysis clarifies the usefulness of CCFT and training in cervical rehabilitation.

References:

- Domenech T, Sizer P, Dedrick G, McGalliard M, Brismée JM. The deep neck flexor endurance test: normative data scores in healthy adults. Phys Med & Rehab. 2011;3(2): 105-110.

- Edmondston S, Björnsdottir G, Pálsson T, Solgård H, Ussing K, Allison G. Endurance and fatigue characteristics of the neck flexor and extensor muscles during isometric tests in patients with postural neck pain. Man Ther. 2011;16:332–8.

- Falla D, Jull G, Hodges PW. Feedforward activity of the cervical flexor muscles during voluntary arm movements is delayed in chronic neck pain. Exp Brain Res. 2004;157:43–8.

- Falla DL, Jull GA, Hodges PW. Patients with neck pain demonstrate reduced electromyographic activity of the deep cervical flexor muscles during performance of the craniocervical flexion test. Spine. 2004;29:2108–14.

- Falla D, Jull G, Hodges P, Vicenzino B. An endurance-strength training regime is effective in reducing myoelectric manifestations of cervical flexor muscle fatigue in females with chronic neck pain. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006; 117:828–37.

- Peréz AH, García ÁF, de Uralde Villanueva IL, et al. Effectiveness of a motor control therapeutic exercise program combined with motor imagery on the sensorimotor function of the cervical spine: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2015;10(6):877.

- Jull G, Falla D. Does increased superficial neck flexor activity in the craniocervical flexion test reflect reduced deep flexor activity in people with neck pain? Man Ther. 2016;25:43–7.

- Jull G, Falla D, Treleaven J, Hodges P, Vicenzino B. Retraining cervical joint position sense: the effect of two exercise regimes. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:404–12.

- Jull GA, O’Leary SP, Falla DL. Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2008;31:525–33.

- Lindstrom R, Schomacher J, Farina D, Rechter L, Falla D. Association between neck muscle coactivation, pain, and strength in women with neck pain. Man Ther. 2011;16:80–6

- Moon HJ, Goo BO, Kwon HY, Jand JH. The effects of eye coordination during deep cervical flexor training on the thickness of the cervical flexors. J. Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:3799-3801.

- O’Leary S, Jull G, Kim M, Uthaikhup S, Vicenzino B. Training mode- dependent changes in motor performance in neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1225–33.

- O’Leary S, Jull G, Kim M, Vicenzino B. Cranio-cervical flexor muscle impairment at maximal, moderate, and low loads is a feature of neck pain. Man Ther. 2007;12:34–9.

- O’Leary S, Jull G, Kim M, Vicenzino B. Specificity in retraining craniocervical flexor muscle performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:3–9.

- Park J, Ko D, Her J, Woo J. What is a more effective method of cranio-cervical flexion exercise? J. Back Musculoskel Rehab. 2018;31:415-423.

- Revel M, Minguet M, Gergoy P, Vaillant J, Manuel JL. Changes in Cervicocephalic Kinesthesia after a proprioceptive rehabilitation program in patients with neck pain: A randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1994;75:895-899.

- Silva F, Brismée JM, Sizer P, Hooper T, Robinson G, Diamond A. Musicians injuries: Upper quarter motor control deficits in musicians with prolonged symptoms-A case-control study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018; 36: 54-60.